In 2004, my father gave me a copy of the memoir of my great-grandfather, Mark Antony DeWolfe Howe (he added the final e to DeWolf, “for tone”). In 1955, my uncle typed up the reminiscences for his siblings. I had no idea it existed, though my brother Mark (he got the full name, less the e for tone) had a copy of it. I nabbed the book and transcribed it into my computer.

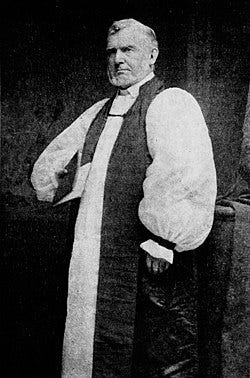

My great-grandfather was born in 1808 and died in 1895, more than two decades before my father (his youngest grandson) was born. He was the Episcopal Bishop of Central Pennsylvania. He most likely wrote with an eye to church history. This made for a hard slog for some of the transcription. In the beginning, there are allusions to his family life, but almost nothing in the last half of the memoirs. My grandfather, the youngest of the 18 children (11 lived to maturity, 2 of his 3 wives died young), is not mentioned at all.

The span from my great-grandfather to me is huge because my grandfather was the youngest of the 18, my father was the youngest of 6 and I'm the youngest of 7.

As I transcribed, I kept my eye out for stories. Here are a few snippets:

MADewH was baptised at age 3. After the baptism, he was taken home. He says that then "all my fine toggery [was] taken off, so that I was left with only a little undershirt on, and when she [the servant who took him home] had gone to get other garments, I slipped out and went into the church again, which was only two doors distant, showing in a very early day my predilection for the church service. My father, hearing the pattering of my little feet, looked in his consternation at my condition, wrapped me in his kerchief and carried me home."

He grew up, went to Middlebury College and Brown University, became a teacher and then was ordained as an Episcopal priest. He married his first wife, Julia B. Amory, in 1834.

Julia fell gravely ill, so he took her to the Caribbean to try to coax her back to health. On the voyage, they went through the Horse Latitudes, called that because when ships had horses on board, they often didn't survive the rough seas. There was a horse on board that was saved because they put it in a sling and padded the stall to protect it. The ship was struck by lightning, and the topmost spars rattled down onto the deck. That trip took 4 weeks, instead of the 10 days.

Alas, Julia died in the Caribbean. My great-grandfather wrote, "In the last few weeks of my wife's continuance, I could scarcely leave her at all, as I had no female friend who could wait upon her [...] and after my wife's breathing ceased, it fell to my lot to close her eyes, and to get out from her trunk the apparel in which she should be clothed. On the next morning, my friend, Mr. Sargent came in to see me, and I shall never forget, he read to me the 103rd Psalm in a very solemn and impressive way. That was the only ministration of a consolatory nature which was given to me at that awful juncture."

He returned home (as did his wife's body, preserved in a cask of rum), grieving terribly. This is one of the saddest parts of the reminiscences.

The last big chunk of the memoir is about the Lambeth Conference of 1878, a gathering of bishops of the Anglican Communion from around the world. He and my great-grandmother took a ship to England, with a whole passel (herd? flock?) of bishops.

On the journey, they were in a stateroom with walls that didn’t reach all the way to the ceiling. In the next room were two "musical gentlemen." MADeWH recalled, "When I awakened in my upper berth on the first morning, I found this opening in the partition between me and my musical friends stuffed with pillows and shawls, and [...] while I was dressing [...], I heard the upper man say to his friend, 'Did you hear the old gentleman blowing his horn all night?' 'No,' said he. 'But I did,' rejoined the complainant, 'I tell you, he’s a regular old steam tug.' So I was enlightened as to the purpose for which the shawls and pillows were stuffed there."

On a similar theme, during a visit to a cathedral:

"In the afternoon of the same Sunday, a preacher of much more soporific influence occupied the pulpit at the Cathedral, while Bishop Littlejohn, Bishop Wilmer and myself occupied stalls in the choir. I became unconscious in the progress of the discourse, and by and by awakened by quite a resonant snore. I looked about to determine, if I might, whether I was the transgressor, and I saw that Bishop Littlejohn and my other friends were doing the same thing, agitated probably by the same solicitude."

What language! People don't speak like this anymore, or not often. I heard remnants of it in the speech of my father, also an Episcopal priest. Within the family, some of us drop into this style from time to time. In general, we don't, because it sounds like affectation. Maybe it is, or maybe it's just habit. It feels as much a part of our family as our big rectangular smiles.

I’m lucky to have this written record of my family. Will I ever make it into a story? Maybe. Do you have family stories from past generations, written or oral?

P.S. You might remember the post I put up about the piece of personal fiction I wrote called The Portraits. Here is the Bishop.

So wonderful that you have this memoir and the snoring so loud someone stuffed pillows and shawls in an opening in order to get some sleep????....makes me wonder if he might have had sleep apnia.

I was able to locate three letters from my great great grandfather. He lived in County Wexford Ireland. The letters were in a cookie tin kept by a distant cousin in Wamego, Kansas.

Wonderful! I love the language! A short story about my grandfather when he came from England to America the first time in the 1920's. As he was getting into New York someone tried to mug him, but he was a good runner, and with his suitcase in hand outran his opponent! He later brought the rest of the family over to the USA but timed it poorly as the crash happened shortly afterwards. They lived in Canada at that time on a farm and survived.